Why inquiry and differentiation?

As an inquiry-based educator, you focus on understanding your students—their curiosity and the questions they have about the world. Your goal is to nurture this curiosity and give them the skills to keep exploring and asking questions throughout their lives.

You also help them discover how they learn best, considering their own interests, readiness, and preferences, so they have the tools to thrive both in the classroom and beyond.

Inquiry and differentiation work hand-in-hand, creating a strong foundation for lifelong learning.

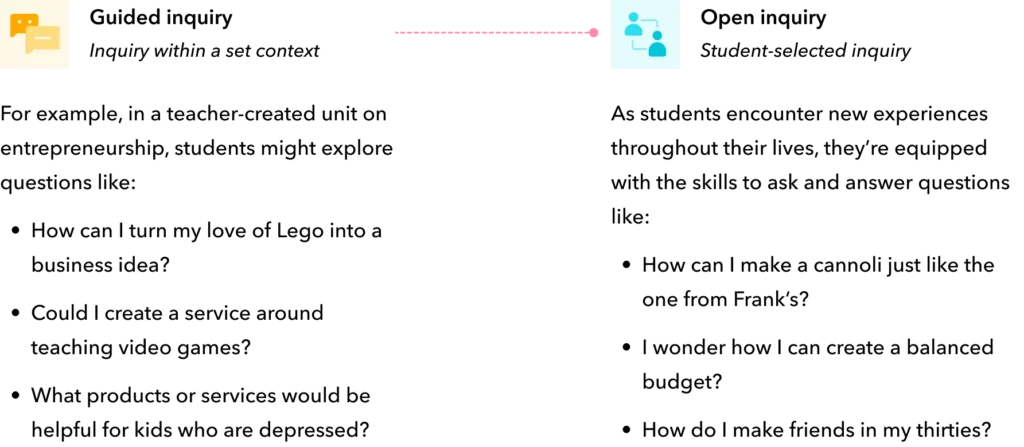

Guided vs. open inquiry

In this article, I will focus on guided inquiry. In a guided inquiry, students form questions within teacher-set goals or themes tied to standards. This approach helps them ask meaningful questions and seek answers independently. As they gain confidence, they can use these skills in more open, self-directed inquiries, becoming curious explorers of the world.

Three steps for differentiating a guided inquiry

The purpose of both differentiation and guided inquiry is to equip students with the knowledge and skills to become lifelong learners. Your goal is to help students thrive not just in your classrooms, but in life beyond school. But how do you practically differentiate an inquiry in your classroom?

Unlike traditional differentiation, in an inquiry-based classroom, you don’t always know what content will be studied from the start. Instead, you begin with student interests and questions, which shape the learning path.

While the guide is organized by steps, remember that inquiry is cyclical—you’ll likely revisit and refine each step as you progress through the inquiry.

Step 1: Define success criteria

As you begin planning a differentiated guided inquiry, the starting point is getting crystal clear on what success looks like. Ask yourself, what will students know, understand, and be able to do as a result of their time in your classroom?

Although there’s plenty of room for student inquiry and personalization in the learning process, our success criteria set the same high expectations for all learners and serve as the foundation for provocation, planning, assessment, and teaching.

You might:

- Review your curriculum and highlight the standards you will focus on.

- Take time to unpack:

- Knowledge: What key facts, vocabulary, or ideas do students need to know?

- Understandings: What are the big ideas or main takeaways?

- Skills: What skills will students develop?

It can be helpful to turn these into student-friendly ‘I can’ statements or create simple, one-point rubrics for clarity.

Try using AI to help you with this step! You can copy and paste your curriculum standards and ask the chat to “unpack these standards into knowledge, understandings, and skills.”

Step 2: Personalize the inquiry

Now that you have a clear picture of what success will look like by the end of the unit, it’s time to consider the exciting task of tailoring the journey to your learners’ needs and interests—the unique paths they’ll take toward reaching these goals.

The beginning of an inquiry is very important. While you have a high level view of what success looks like, an inquiry doesn’t truly begin until each student has a unique question they are eager to explore.

Tomlinson’s (2014) framework for differentiation provides a beautiful starting point for planning an inquiry, inviting educators to consider each learners’ interest, readiness, and preferences.

Let’s dive into each of these elements and discover how you might use them to begin planning an inquiry.

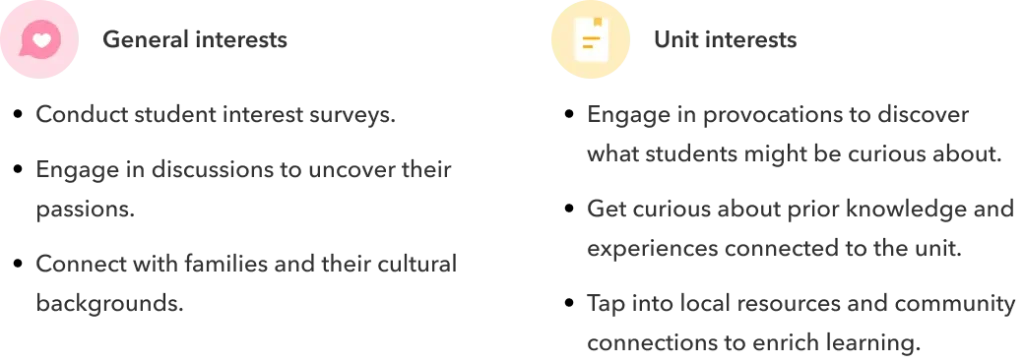

Interests

What do your students like learning about?

Understanding your learners’ interests—both generally and within a unit—is essential to both inquiry and differentiation. The more you know your students, the easier it is to find connections, making learning meaningful and foster a sense of belonging throughout the unit.

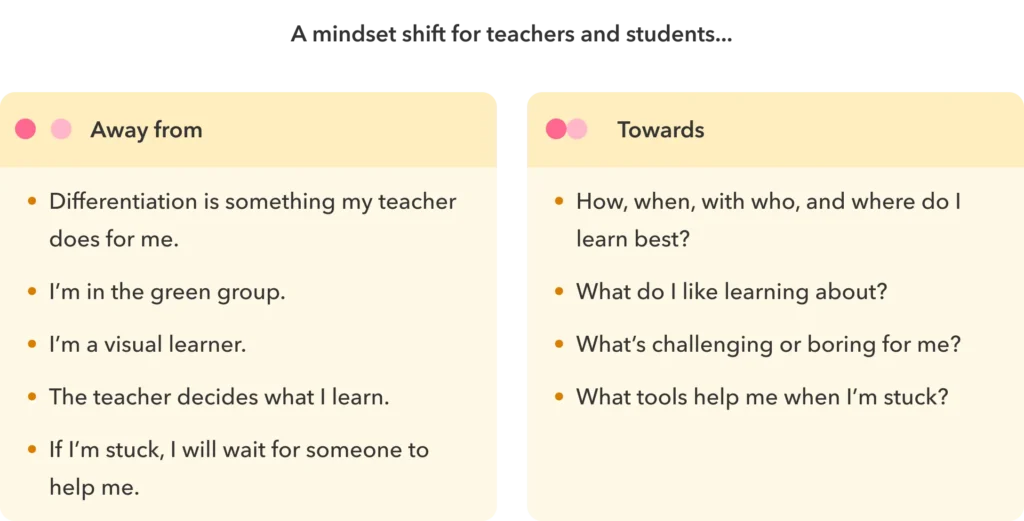

Learning preferences

How might students learn best?

Rather than focusing on fixed learning styles, you can differentiate by considering learning preferences and variability. Encouraging students to explore how, when, where, and with whom they learn best recognizes that these preferences can change depending on a number of factors including the subject and even time of day!

Readiness

What barriers might stand in the way of learning?

Readiness is not fixed. As teachers, you should stay curious about what students know, understand, and can do, always aware of their strengths and areas for growth. It’s important not to pigeonhole students.

To truly understand where your learners stand, you need pre-assessments connected to your learning goals. With a full picture of their strengths and challenges, you can plan responsive supports and enrichments.

Readiness is multi-faceted! You could consider:

- Content knowledge

- Language

- Emotional maturity

- Academic skills

- Creativity

- Collaboration

- Self-expression

- Confidence

- Time or task management

- Reflection

For example, Jamie might be considered a ‘beginner’ in business concepts, yet excels at coming up with creative product ideas and expressing them with enthusiasm. However, he might need support with managing time effectively or building confidence when it comes to organizing his ideas into a business plan.

Step 3: Scaffold the inquiry

Once you’ve identified students’ burning questions (interests), the obstacles they face (readiness), and how they learn best (preferences), you can begin crafting learning experiences, scaffolds, and extensions to move the inquiry forward.

At this stage, you step into the role of facilitator, using the elements of content, process, product, and environment to design a learning setting that supports students in answering their questions and reaching their goals.

Let’s dive deeper into each of these factors:

Scaffolding the learning environment

How do I create flexible and equitable spaces for learning?

A major part of building an inquiry environment involves setting the stage with your learning environment design. The list of considerations I’ve provided is by no means comprehensive! You and your students spend an incredible amount of shared time in the classroom, so it’s essential to establish clear norms around the tools and resources available for learning.

By thoughtfully arranging these elements, you can create a classroom environment that actively supports student engagement and growth.

Think about:

- Are there flexible options for where students work?

- Is there access to quiet spaces or noise-canceling headphones for those who need a quieter environment?

- Are there gathering spaces equipped with collaborative tools like chart paper, whiteboards, or other resources for group work?

- Are there tools or other equipment available that support their specific inquiry?

- Do students have access to support materials like manipulatives, with clear guidelines on their use?

- How is access to technology managed within the space?

- Are there opportunities for learning outside of the classroom?

- Do all students know the norms, expectations, and opportunities?

Scaffolding content

How will students access new information?

Imagine you’re learning to make a new recipe. How do you learn best? Some of us prefer a video that shows each step, while others might turn to a blog or cookbook. Now, switch gears to learning a new language. Would you use the same method to learn French that you used to bake? Probably not!

The same principle applies to our learners. When you differentiate content, ask yourself, what’s the best way for each student to access new information? While all students are expected to gain the same knowledge, understandings, and skills, there is flexibility in how they access that information.

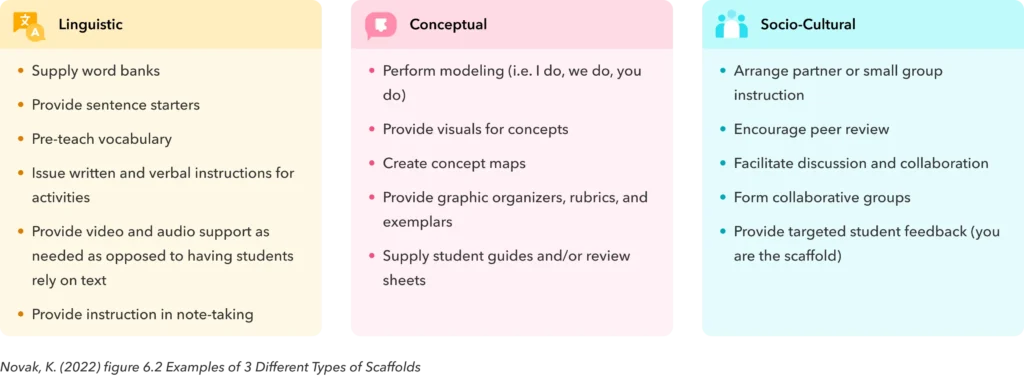

One helpful framework for scaffolding content comes from Katie Novak, who suggests three types of scaffolds: linguistic, conceptual, and socio-cultural. These can be used to effectively engage students as they build their understanding.

By considering students’ readiness, interests, and preferences, you can offer a range of scaffolds for them to choose from as they work. Katie also recommends limiting choices to no more than six options, as too many choices can become overwhelming!

Scaffolding the process

How will students make sense of new knowledge, understanding, and skills?

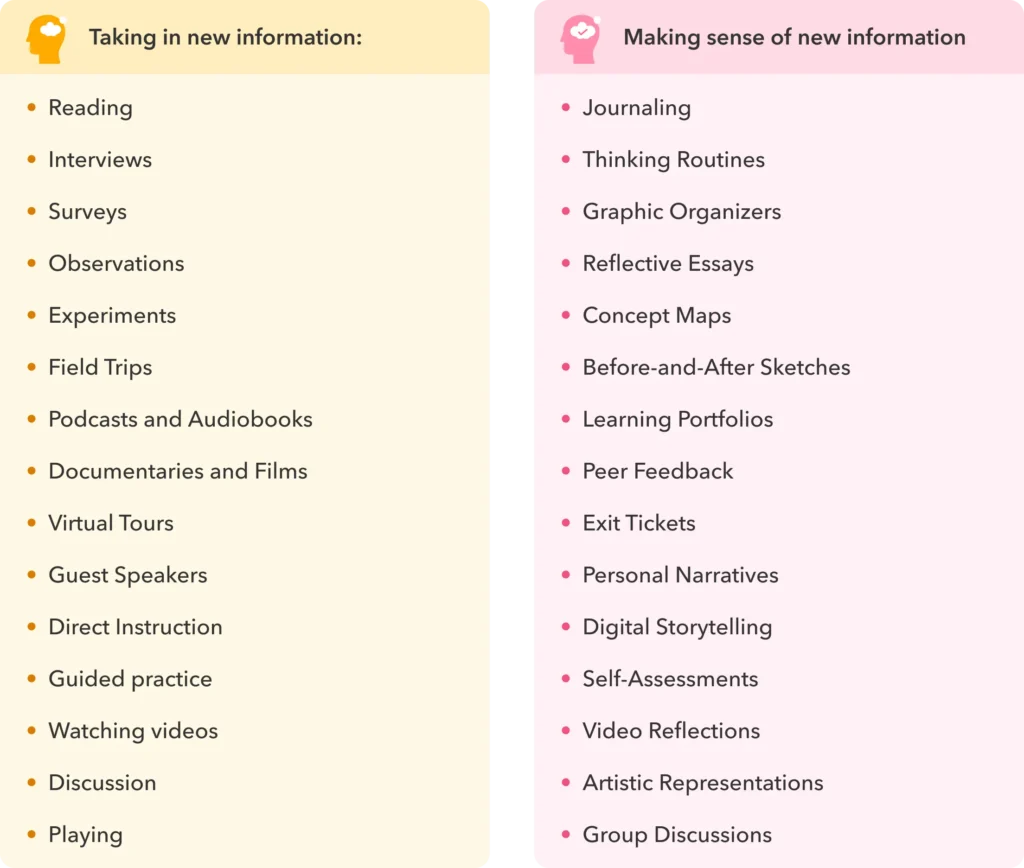

Processing involves two main aspects: taking in new information and making sense of it. When planning for processing, I consider two essential questions:

- Taking in new information: How might each student develop this knowledge, understanding, or skill?

- Making sense of new information: How might each student show and reflect on how their thinking has changed as a result of the learning?

Your goal is to offer a range of options that accommodate students’ learning interests, preferences, and readiness, ensuring personalized pathways within their learning experiences.

Scaffolding the product

How will students apply their knowledge, understandings, and skills?

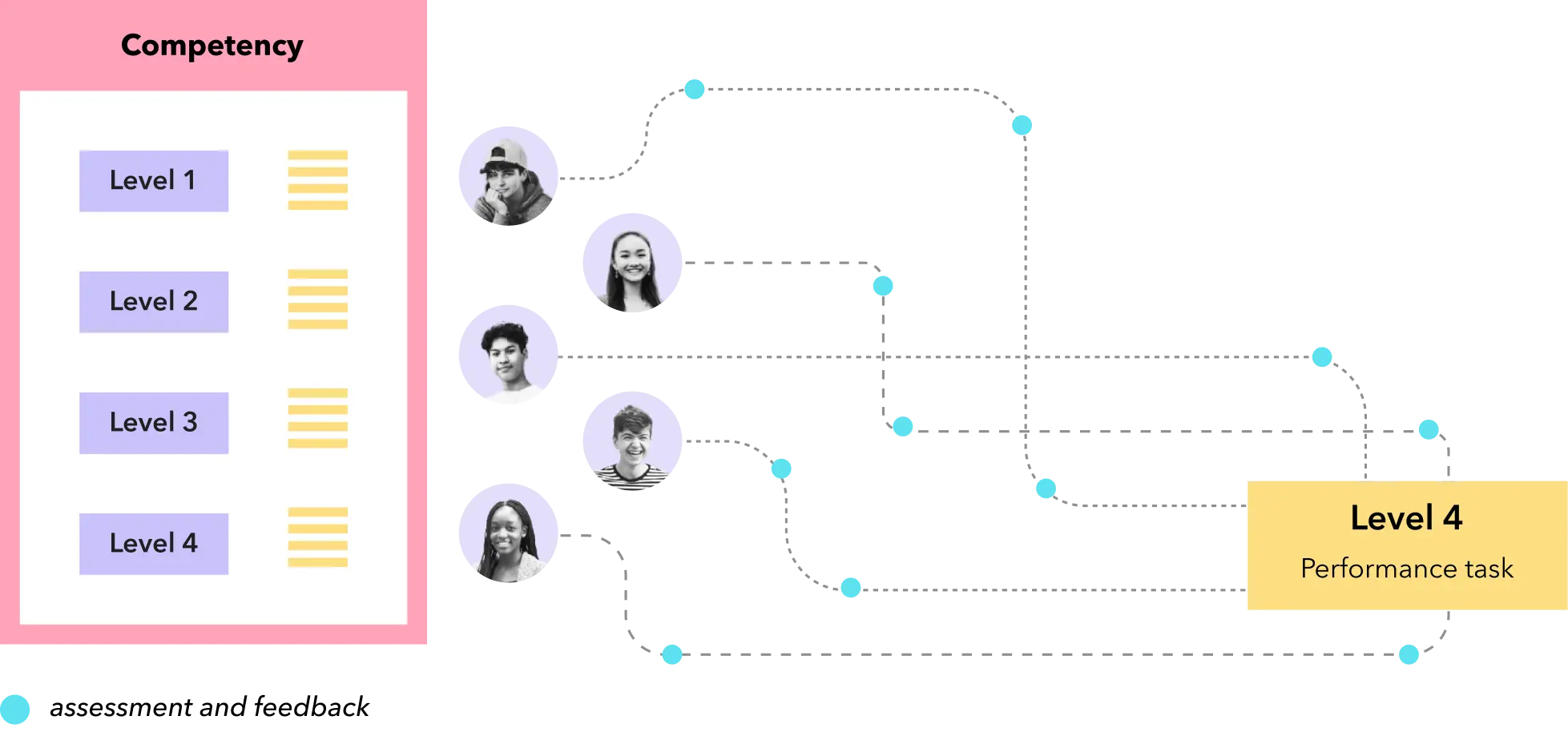

Products make up only a small portion of your assessments. In differentiated inquiry, the majority of your time is spent on processing information and providing ongoing, actionable feedback.

You can think of a product as a milestone in the inquiry process—an opportunity for students to showcase and apply the knowledge, understandings, and skills they’ve developed along the way.

When designing these learning experiences, the guiding question becomes: How will I know students have mastered the success criteria? You can give students choice and flexibility in how they demonstrate their learning, as long as it aligns with the goals you identified in step one.

A product might be:

- Presentations (oral, digital, or multimedia)

- Videos or documentaries

- Blogs or news articles

- Posters or infographics

- Podcasts or audio recordings

- Storybooks or comic strips

- Models or dioramas

- Art pieces (paintings, sculptures, or digital art)

- Research papers or essays

- Digital portfolios

- Students’ choice!

Remember, it’s a cycle!

In this guide, I’ve outlined three major phases for planning an inquiry:

- In step 1, you aligned with our curriculum and clearly defined success.

- In step 2, you focused on our students, exploring how to make the learning experience relevant and engaging for them.

- In step 3, you examined the learning process, supporting students as they pursue their burning questions.

Although presented in steps, it’s important to remember that both inquiry and differentiation are cyclical. You’ll likely revisit these phases multiple times as students progress and learn throughout the inquiry.

References

ASCD. (2011). Differentiation for Readiness. https://pdo.ascd.org/LMSCourses/PD11OC138M/media/DI-Instruction_M4_Reading_Readiness.pdf

Brown, M., Holeton, R., & Long, P. (2017). Learning Space Rating System. https://acode.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Educause-Learning-Space-Rating-System-1.pdf

Kaufman, S. (2020). Transcend : the new science of self-actualization. Tarcherperigee.

Novak, K. (2022). UDL now! : a teacher’s guide to applying universal design for learning in today’s classrooms. Cast Professional Publishing.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Toddle School Leaders Project. (2024). How to differentiate learning in your schools? | Carol Ann Tomlinson. Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9P0cJUEPThY

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). Alexandria, Va Ascd.Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating Instruction in Response to Student Readiness, Interest, and Learning Profile in Academically Diverse Classrooms: A Review of Literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2-3), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320302700203